Forty-five years ago, for the very first time behind the Iron Curtain, ordinary citizens took matters so effectively into their own hands that the authorities had no choice but to yield, sit down at the table and negotiate the terms of social peace with the workers. The agreement that followed gave rise to the first trade union in the Soviet sphere of influence that was independent of the communist authorities. Owing to Solidarity, the Republic of Poland was reborn as the democratic and sovereign state it is today.

The events that led to the collapse of communism in Europe were sparked in Gdańsk but the whole country was seething. What was at stake?

Authorities Grown Complacent

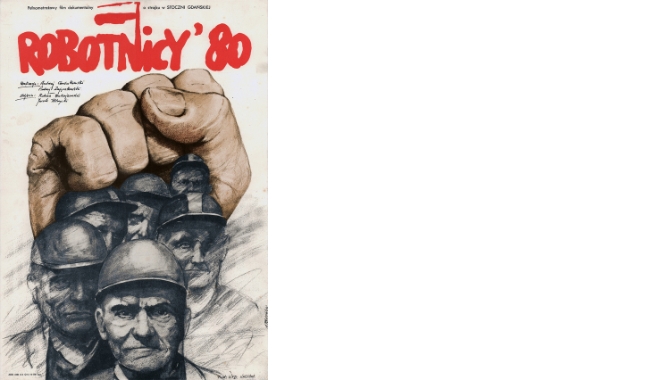

The extent of social discontent was voiced by the workers themselves, looking straight into the camera. These images were used in Workers ‘80, a 1980 full-length black-and-white documentary which chronicled the strike at the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard and the negotiations between the strikers and the authorities (directed by Andrzej Chodakowski and Andrzej Zajączkowski).

‘What weapon do we have now, other than to strike? We’re all fed up with all of this,’ says one worker. ‘We’ve had enough of the lies all these years and want to set things straight,’ adds another. More voices followed: ‘No one wants a change of government or a change of system but the economy must be pulled out of this crisis.’ ‘They must reckon with the workers because we are the ones who create the nation’s wealth.’ ‘The Polish worker . . . has learnt to read, to write, . . . change needs to come gradually and we ourselves have already changed a bit. The Party, the authorities should grow alongside the worker if they want to live with us together and in a way that makes sense.’ ‘And perhaps a little more humility, if we may ask our leaders, a little humility.’ ‘They’ve grown far too complacent and need a serious jolt.’ ‘And they shouldn’t proclaim themselves, as some of our leaders do, to be “good Poles,” “patriots” or “communists.” One shouldn’t boast about oneself; one should wait for the opinion of other, competent people.’

The Spark

On 7 August 1980, Anna Walentynowicz, a gantry crane operator at the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard, was summarily dismissed just months before she was due to retire. She was not the first to suffer harassment and reprisals. In January, Andrzej Kołodziej had been dismissed from the Gdańsk Shipyard; in February, Lech Wałęsa was removed from Elektromontaż (he had been handed a notice of termination from the Gdańsk Shipyard back in 1976); in March, several more workers were sacked from the Northern Shipyard. But Walentynowicz was different: she was well known, respected and active in the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (WZZ). Her dismissal was clearly a punishment for her opposition work. To make the injustice worse, she had been employed at the Shipyard since 1950 and, during the era of ‘labour heroes,’ had been working at 270% of her output quota.

Opposition activists decided to hold a strike in defence of the persecuted activist. The start date was set for 14 August. The plan was drawn up by Bogdan Borusewicz, an opposition member of the WZZ and a history graduate of the Catholic University of Lublin. The task of launching the protest inside the Shipyard fell to three young workers: Bogdan Felski, Jerzy Borowczak and Ludwik Prądzyński.

At dawn that day, as the workers made their way to their shifts, an information campaign began. Leaflets circulated hand to hand so that, by the time they entered the plant, everyone knew what had prompted the protest. After six o’clock, worker by worker, department by department, they left their stations.

The Memory of Bloodshed

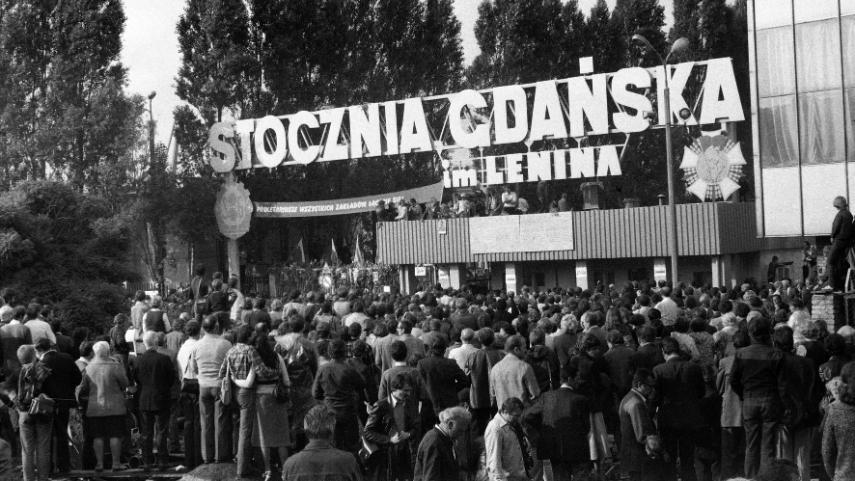

The Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard—the largest enterprise in northern Poland—was a force in itself. Sheer numbers gave workers a sense of security: after all, they could not all be sacked or arrested. The Tri-City of Gdańsk, Gdynia and Sopot was also home to active opposition circles, such as the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (WZZ), the Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR), the Movement for Defence of Human and Civic Rights (ROPCiO), and the Young Poland Movement (RMP). And, in Gdańsk, the memory of the workers killed ten years earlier served as a powerful bond. The anniversaries of the December 1970 revolt were commemorated with demonstrations, demanding the truth about the reprisals and calling for a monument in honour of those killed. In December 1979, several thousand gathered at the Shipyard’s Gate No. 2. It was a clear sign of how deeply the memory of the workers’ protests resonated with the people of Gdańsk.

The young shipyard workers who launched the strike made sure the workforce did not take to the streets. The protest took the form of a sit-in, a lesson learnt from the bloodshed of ten years before.

Lech Wałęsa, once an employee, proved to be a charismatic leader and became the head of the movement.

Solidarity Strike

The workers formed a strike committee and put forward their demands: the reinstatement of Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa, pay rises and commemoration of those killed in December ‘70. Soon, other workplaces in the Tri-City area began to join the protest. On 16 August, the shipyard director agreed to meet the demands, and Wałęsa—authorised by the strike committee—declared the protest over. But the crews of other plants that had joined the strike were not satisfied with that turn of events. They feared—and rightly so—that without the moral weight of the great shipyard behind them, they would be exposed to a violent crackdown by the authorities. Meanwhile, the Shipyard workers, satisfied with the positive outcome of the negotiations, began heading for the exits. The strike was saved by women: Alina Pienkowska, Anna Walentynowicz, Ewa Ossowska and Henryka Krzywonos ran to turn the workers back from the gates. They persuaded Wałęsa that the protest must continue. He announced a solidarity strike with the other plants but only a few hundred workers remained in the Shipyard. Despite this, on the night of 16–17 August, the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (MKS) was established, led by Lech Wałęsa, to coordinate the demands and strike action.

That same night, the MKS drew up one of the most significant social documents of the 20th century: the 21 Demands, articulating social needs and the pursuit of pluralism, self-determination, dignity and civil liberties, including freedom of association and expression.

The days that followed were crucial to sustaining the protest.

The Gate That Unites

The final shape of the 21 Demands owed the most to Bogdan Borusewicz, who grouped and ranked them in order of priority. At the forefront were the political demands: the right to form independent trade unions, the abolition of censorship, guarantees of safety for strikers and the release of political prisoners. The strike demands became a shared platform for struggle that each workplace had previously waged on its own. To disprove the official narrative spread by state-controlled media that the demands were solely economic and not broadly social, and to make them public property, opposition activists from the RMP—Arkadiusz Rybicki and Maciej Grzywaczewski—wrote them out on wooden boards. These were put up outside, on the access pass office at the Gdańsk Shipyard’s Gate No. 2.

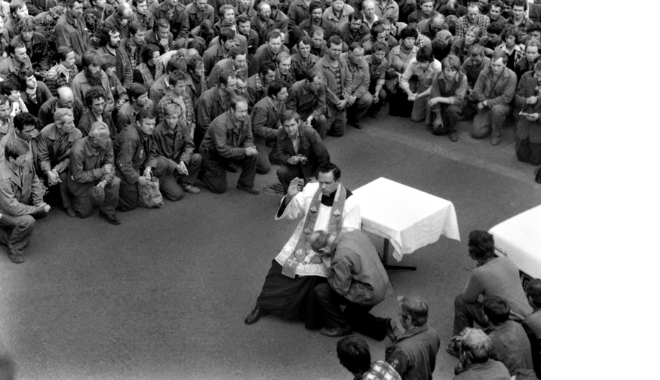

Gate No. 2 was a powerful symbol of the strike. During the December 1970 protest, it was there that the shipyard workers participating in the strike had been shot dead or wounded. The gate became the first site of remembrance for them. In August 1980, people decorated it with an image of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa and a portrait of Pope John Paul II; visitors adorned it with flowers. Gate No. 2 did not divide but united the striking shipyard workers and the crowds gathering in front of it to support the protest. During the strike, the gate was a popular meeting place for protesters and their families. It was through there that aid—food, medicine and money—flowed into the Shipyard. Close to it, prayers and masses were held, drawing crowds of thousands.

God, Thou Who Hast Poland

The strike that began at the Gdańsk Shipyard was steadily joined by other Tri-City plants, including the Paris Commune Shipyard in Gdynia, the Gdańsk Municipal Transport Company (ZKM), the ‘Heroes of Westerplatte’ Northern Shipyard in Gdańsk, and the Elmor Ship Electrical Appliances and Automation Works. Soon, the protests spread across Poland. Inter-Enterprise Strike Committees (MKSs) were formed in other cities, such as Szczecin, Jastrzębie and Katowice.

But the proclamation of the Solidarity Strike, the establishment of the MKS and the drafting of the 21 Demands did not in themselves guarantee the protest’s success. Emotions ran high: from faith in victory to fear and discouragement. Spiritual support became vital. On 17 August, Rev. Henryk Jankowski, parish priest of nearby St Bridget’s, celebrated Mass inside the Gdańsk Shipyard. On the other side of the gate, families of the strikers, Tri-City locals and visitors gathered in droves . . . Their common lot, expressed through religious tradition, bound together the strikers and the crowd gathered outside the gate. White-and-red flags, the portrait of John Paul II on the gate, the Polish anthem led by Wałęsa, the hymn God, Thou Who Hast Poland (Boże, coś Polskę), and prayers led by Bożena Rybicka and Magdalena Modzelewska all reinforced the belief that they were fighting for common goals. Shaped around shared symbols, the movement forged its own ethos, rooted in cultural traditions born of shared experience. Passive resistance, non-violence and a ban on alcohol gave the Gdańsk Shipyard strike an ethical dimension, expressed in civil disobedience against arbitrary decisions made by the state authorities without consultation with society.

Western Media

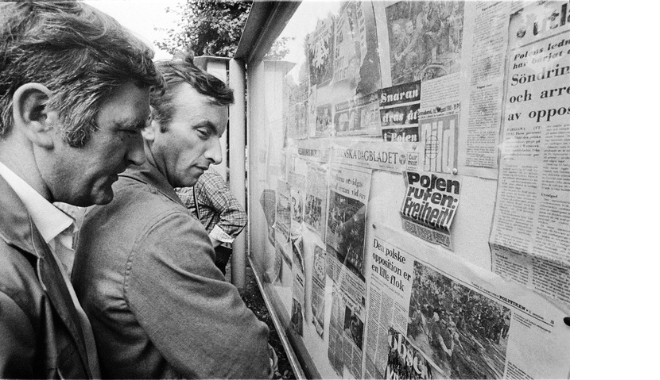

Opposition activists made possible the first use of underground printing during the August strike at the Gdańsk Shipyard. The backbone of the strike’s press operation in the Tri-City was the Gdynia Shipyard’s Free Printing House, from which large-scale production of leaflets and underground publications was launched. This not only countered the regime’s disinformation campaign but also enabled the rapid flow of information through a distribution network that linked one workplace to another. A central role was played by the Strajkowy Biuletyn Informacyjny Solidarność (Solidarity Strike Information Bulletin), which covered current affairs and included strike poetry, interviews and reports. Its daily circulation reached about 40,000 copies.

News of what was happening in Gdańsk spread not only among workers and local residents but also broke through to foreign media, owing to Western correspondents on the ground. Their reports, alongside interviews with strike leaders, were broadcast by Radio Free Europe. For many weeks, the front pages of leading magazines in Germany, France and the United Kingdom were dominated by the story of the August protests. Captured in photographs by Western photojournalists, the flower-adorned Gate No. 2 became a worldwide icon of the August strike. Lech Wałęsa and Anna Walentynowicz were the central figures of many articles. Letters of support and significant sums of money began arriving at the Gdańsk Shipyard from trade unions across nearly all of Western Europe and the United States.

One Supporting the Other

The word ‘Solidarność,’ written in an original typeface that later came to be known as Solidarics (Solidaryca), became a symbol recognised around the world. Jerzy Janiszewski, a graphic artist trained at the State Higher School of Fine Arts (PWSSP) in Gdańsk, began working with his wife on a design that would support the strikers in their common struggle. A poet drew his attention to a word that was frequently written on walls. And so Janiszewski put the word ‘Solidarność’ across a white background. The letters symbolised a crowd of people, pressed close, supporting each other. Above them, he added the white-and-red Polish flag because, by then, the strike had already grown into a nationwide uprising.

As the situation at the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard escalated and an increasing number of workplaces voiced support for the strike demands, the government decided to enter into negotiations with the workers. It was publicly announced that a special commission ‘to examine the demands of the workforces and the problems of the Coast’ had been established, chaired by Deputy Prime Minister Tadeusz Pyka. Alongside the proposal to negotiate, the authorities were also preparing for a possible use of force. Under Operation codenamed Summer–80, the Ministry of Internal Affairs sought to curb the influence of the opposition representatives on the striking workers, targeted so-called ‘organised antisocialist elements,’ and closely monitored the strike at the Gdańsk Shipyard and other protesting workplaces across the Tri-City area. The government’s true intention was not to reach an agreement with the strikers but to extinguish the protests, which is why the negotiations led by Pyka’s commission failed to produce the expected results. Deputy Prime Minister Mieczysław Jagielski, who replaced Pyka as head of the government delegation, initially followed a similar strategy, holding talks separately with representatives of each workplace while ignoring the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (MKS). The turning point in the negotiations came when Jagielski signed a written receipt of the strike demands. In doing so, he had granted formal recognition to the MKS. This occurred on 22 August.

Alliance of Workers and Intelligentsia

The support of the intelligentsia for the striking workers had a major impact on the course and character of the negotiations. On 20 August, Radio Free Europe announced the publication of the Appeal of the 64: in Warsaw, scholars, writers and journalists urged the authorities to find a solution that would prevent bloodshed and to recognise free trade unions. The appeal was addressed to both the political leadership and the striking workforce at the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard. The document was brought to Gdańsk by Bronisław Geremek, a historian with the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Institute of History in Warsaw, and Tadeusz Mazowiecki, vice-president of the Warsaw Club of Catholic Intelligentsia (KIK). Lech Wałęsa entrusted them with forming a group of experts, which included five more signatories of the Appeal of the 64: sociologist Jadwiga Staniszkis, Znak magazine columnist Bohdan Cywiński, president of the Warsaw KIK Andrzej Wielowieyski, and economists Waldemar Kuczyński and Tadeusz Kowalik. At first, the Gdańsk Shipyard workforce regarded the experts with some mistrust but the workers–intelligentsia alliance soon became a reality, shaping both the tone and conduct of the negotiations. The team of experts gave the talks with government representatives a professional character.

Safety Guarantees

A second strike centre emerged in Szczecin, at the Warski Shipyard. Its leader, Marian Jurczyk, like Wałęsa, had taken part in the protests of the December 1970 revolt in Szczecin. There too, an Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (MKS) was formed and a list of 35 demands was drawn up. But unlike in Gdańsk, journalists were not admitted to the Shipyard, nor was there collaboration with the local democratic opposition. Negotiations in Szczecin, as in Gdańsk, were conducted by Kazimierz Barcikowski on behalf of the state authorities, directly with Jurczyk. On 26 August, Poland’s largest plant, the Lenin Steelworks in Kraków, joined the strike, as did Poznań’s Cegielski Works, known for its role in the 1956 protests. In Wrocław, another MKS was formed which fully endorsed Gdańsk’s 21 Demands. The strike swept across the country. By 29 August, plants in Upper Silesia, in southern Poland, had downed tools. Faced with a nationwide social uprising, the authorities backed down. They signed an agreement in Szczecin and ultimately consented to the model of free, independent trade unions. The government’s acceptance of the first two Gdańsk demands became a turning point in the talks, on 30 August.

Yet one point of contention remained: safety guarantees for the strikers. Andrzej Gwiazda, whose demands Lech Wałęsa presented to Jagielski’s Commission, insisted on such guarantees, threatening that the strike would continue unless the opposition activists were released. On that day, according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ statistics, the number of protesters exceeded 700,000, with more than 750 plants taking part in the August strike.

The release of those arrested paved the way for the signing of the Gdańsk Agreement at the Gdańsk Shipyard. The day was 31 August 1980.

We Will Have More Rights Established Soon

With an oversized pen featuring the image of Pope John Paul II, Lech Wałęsa was the first among the members of the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (MKS) to sign the Gdańsk Agreement. Then, from atop Gate No. 2, he announced the ratification of the demands and, at the strike’s close, said: ‘At last, we have independent, self-governing trade unions! We have the right to strike! And we will have more rights established soon!’

In Silesia, the strikes continued longer. On 3 September, an agreement was reached at the Manifest Lipcowy Coal Mine in Jastrzębie-Zdrój and, on 11 September, at the Katowice Steelworks in Dąbrowa Górnicza. Government officials concluded a social contract with the newly formed movement—a phenomenon unprecedented in the Eastern Bloc. Workers had won both the right to organise independently of the authorities and the right to strike, as a means of holding the authorities to account.

A decisive moment for the organisation of the new trade unions came on 17 September 1980, at the Gdańsk congress of representatives of the Inter-Enterprise [trade union] Founding Committees, which had grown out of the MKS. A decisive step was then taken to establish a single nationwide union, rejecting a proposed federated structure. Put forward by Karol Modzelewski, the organisation’s name, Solidarność (Solidarity), was also accepted, with its full form: Independent Self-Governing Trade Union ‘Solidarność.’ A provisional governing body was formed: the National Coordinating Commission (KKP), with Lech Wałęsa as its chair.

By 1981, on the eve of martial law, Solidarity had reached a record membership of 10 million people out of Poland’s 12 million wage earners, representing about 80 per cent of the country’s entire workforce.